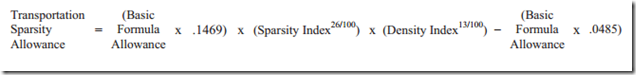

I’m with Atrios here (warning: profanity). The easiest part of computing your taxes is the calculation of tax from Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) facilitated by the tax tables. You could have one bracket, ten brackets, a hundred brackets, or an elliptic curve; the lookup tables make that computation simple, and the fact that most people use computers to e-file means that it takes a fraction of a second to compute even the most complex of tax brackets. Even my most favorite calculation in all of government, Minnesota’s transportation sparsity formula, is a cinch to calculate in no time:

No, the complexity of the tax code comes from all the random deductions and credits that exist. Those are the million questions that are asked of your when you use a computer program to fill out your taxes; those are questions 8 through 61 on your friendly 1040 form; those are the countless other forms you need to fill out to calculate your true AGI. That’s the real time-sink, and if you eliminate all those adjustments, deductions, and credits, you will save real time and make the tax code much simpler.

So why don’t we get rid of all that extra stuff? Well, for one thing, most of those deductions are credits are very popular: the 401(k) exclusion, the mortgage interest deduction, student loan interest deduction, capital gains exclusion on the sale of homes, charitable contribution deduction, local tax deduction…lots of people (including me) take advantage of them. Plus, you have an asymmetry of incentives here: if a tax loophole that I can’t take advantage of ultimately costs the vast majority of American’s only $1 but enriches a select few to the tune of $1,000 a year, who is going to be more vocal in terms of deciding that deduction’s fate?

Of all the reasons to reduce the number of tax brackets in our tax code, simplification is not a legitimate one.